Mwandama dreams big

Mwandama in Zomba is engulfed by tobacco and coffee estates owned by city-based barons, but groundnuts and soya are widely produced by local farmers.

The peasants churn out truckloads often sold at low prices dictated by roaming buyers with illegal adjustable scales.

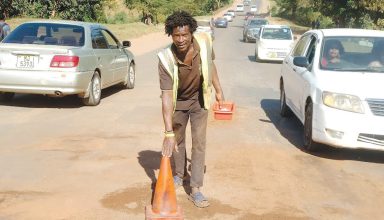

“Many farmers get a raw deal because they sell unprocessed produce for low prices amid rising farm inputs’ prices,” says Smith Mulewa.

He is the chairperson of Mswaswaswa Cooperative comprising 35 farmers determined to profit from their back-breaking toil.

Founded in 2012, the group sell their produce together with scanty processing or value addition.

“By putting together our yield, we bargain for better prices than any of us can get individually. We keep it until the demand spikes,” Mulewa says.

In 2022, their dream to produce peanut butter received a K10 million boost from the Malawi Watershed Services Improvement Project (Mwasip) funded by the World Bank through the Malawi Government.

The matching grants benefit farm-based enterprises uniting up to 15 subsistence farmers’ households.

The cooperative plans to buy machines for not only shelling, peeling and roasting groundnuts but also making peanuts.

“We will also buy aprons, 5000 bottles, stickers, salt and sugar,” he says.

The grant marks the beginning of the end of their long search for capital to turn their dreams into reality.

Truckloads of peanut butter arriving from as far as Lilongwe, almost 400km away, bolsters their hope to excel.

“We want to uplift rural farmers who sell their groundnuts on the cheap and pay exorbitant prices for peanut butter from their own toil,” he says.

Agricultural extension worker Gerald Sawerengera is excited that the group has approached the Malawi Bureau of Standards to ensure their packaged offerings are up to standard.

He sees the farm-based factory creating a market for the farmers who cannot meet the quantity and quality buyers demand.

“With increased revenue from value addition, we will challenge them to produce quality yields and sell more,” he says.

Mwasip targets 100 smallholder farmer groups like Nswaswaswa receiving $5 000 to $25 000 each. Thirty agri-enterprises are earmarked to get $25 000 to $50 000.

By April, the project had disbursed K891.1 million, with K468.1 million injected in 37 farmer groups of 957 people and K423 million to the bigger groups.

Nswaswaswa is one of the 10 farm-based cooperatives under the Mwandama Cooperative Union, which has spread to Zomba, Phalombe and Chiradzulu districts since 2015.

The union’s business plan won a K36 million grant, which includes K4 million from group members.

The farmers say this is a timely jump-start for the community that suffered economic paralysis when machines roared to a stop following a shock breakdown of its electricity transformer.

“We will use K5.5 million to replace the transformer burnt two years ago; K7.6 million to drill a borehole to provide clean water for 5 000 households and 800 students at a nearby school; and K6 million for purchasing a machine for roasting soybeans to produce nutritious flour for school meals.”

“The restored electricity supply will power the milling of nutritious soya flour to be sold to schools. The free school meals are credited with increasing school enrolment, attendance, performance and retention among children from poor families.

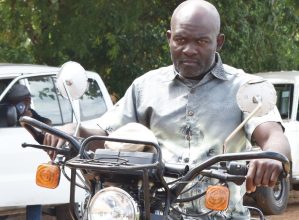

“The cooperative union provides farm inputs for which the farmers pay back when they sell their soya, beans, groundnuts and maize to us, but we didn’t have a mill to process and add value to the produce,” says Kawandama Cooperative business manager Bornwell Kaunga.

The group has invested K20 million in a mill house under construction.

Its is optimistic that the investment will restore the rural economic zone’s rise triggered by the Millennium Village programme backed by the United Nations.

“We want to liberate farmers from vendors who offer low prices to maximise profits. We want growers to win. With processing and value addition, we can sell for more and pay back more,” says Kaunga.

Mwandama Cooperative strives to beat the prevailing minimum buying prices for crops, including farmgate prices announced by the Ministry of Agriculture.

“Last year, maize was selling at K345 a kilogramme, but we got it at K600 from our farmers,” Kaunga explains.

About seven of every 10 members of the affiliated cooperatives are women.

Board member Maria Nachiola, says: “Women are vital in our dream for Mwandama to start producing fortified maize flour widely known as Likuni Phala and soya flour for school meals.

“We have a long-term plan to become cooking oil to create jobs, reward farmers often short-changed and help the nation save the Forex wasted on goods we can produce locally.”

For over a decade, Mwandama was a beacon of hope. From afar, visitors saw the locals hard at work in their fields draped in healthy crops mostly fed with manure. After harvesting, they put together their harvest for household consumption and for sale at better prices that each could negotiate single handedly.

The spirit has survived beyond the deadline of the Millennium Village project. The locals are united under cooperatives that enhance their access to capital, farm inputs and lucrative markets.

“With unity, we can achieve much more than each one of us will ever do. We win together and we take care of the environment together,” says Mulewa.n